From requirements discovery to release

Every time we start a greenfield software project, we are faced with the overwhelming responsibility of creating something from nothing. Because the path from the requirements discovery phase to the first release of a product has so many unexpected twists and turns, the whole process can feel a bit unforgiving and magical. This feeling is a big part of what makes programming hard, even for experienced developers.

For the longest time, I relied heavily on my intuition to get myself kick-started on new projects. I didn’t have a clear sense of what my creative process was, but I could sense that my fear of the unknown started to melt away as I gained more experience as a programmer. Having a bit of confidence in my own abilities made me more productive, but not knowing where that confidence came from made it impossible for me to cultivate it in others. Treating my creative process as a black box also made it meaningless for me to compare my approach to anyone else’s. Eventually, I got fed up with these limitations and decided that I wanted to do something to overcome them.

My angle of approach was fairly simple: I decided to take a greenfield project from the idea phase to an initial open source release while documenting the entire process. I thought this information might provide a useful starting point for identifying patterns in how I work and also a basis of comparison for other folks. As I reviewed my notes from this exercise and compared them to my previous experiences, I was thrilled to see that a clear pattern did emerge. This article summarizes what I learned about my own process; I hope it will also be helpful to you.

Brainstorming for project ideas

The process of coming up with an idea for a software project (or perhaps any creative work) is highly dynamic. The best ideas tend to evolve quite a bit from whatever the original spark of inspiration was. If you are not constrained to solving a particular problem, it can be quite rewarding to allow yourself to wander a bit and see where you end up. Evolving an idea is like starting with a base recipe for a dish and then tweaking a couple ingredients at a time until you end up with something delicious. The story of how this particular project started should illustrate just how much mutation can happen in the early stages of creating something new.

A few days before writing this article, I was trying to come up with ideas for another Practicing Ruby article I had planned to write. I wanted to do something on event-driven programming and thought that some sort of tower defense game might be a fun example to play with. However, the ideas I had in mind were too complicated, so I gradually simplified my game ideas until they turned into something vaguely resembling a simple board game.

Eventually, I forgot that my main goal was to get an article written and decided to focus on developing my board game ideas instead. With my wife’s help, over the course of a weekend I managed to come up with a fairly playable board game that bore no resemblence to a tower defense game and would serve as a terrible event-driven programming exercise. However, I still wanted to implement a software version of the game because it would make the experience much easier for us to analyze and share with others.

My intuition said that the project would take me a day or so to build and that it’d be sufficiently interesting to take notes on for my “documenting the creative process” exercise. This gut feeling was enough to convince me to take the plunge, so I cleared the whiteboards in my office in preparation for an impromptu design session.

Establishing the 10,000-foot view

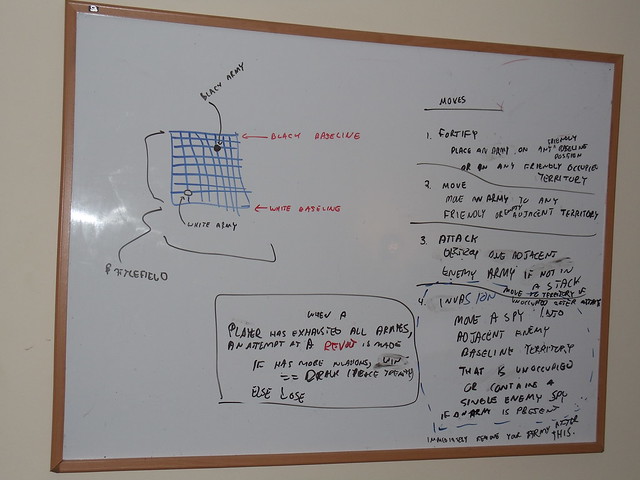

Whether you’re building a game or modeling a complex business process, you need to define lots of terms before you can go about describing the interactions of your system. When you consider the fact that complex dependencies can make it hard to change names later, it’s hard to overstate the importance of this stage of the process. For this reason, it’s always a good idea to start a new project by defining some terms for some of the most important components and interactions that you’ll be working with. My first whiteboard sketch focused on exactly that:

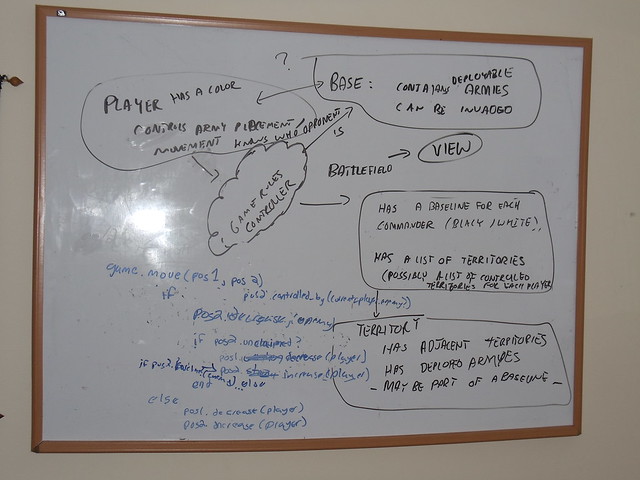

Having a sense of the overall structure of the game in somewhat more formal terms made it possible for me to begin mapping these concepts onto object relationships. The following image shows my first crack at figuring out what classes I’d need and how they would interact with each other:

It’s worth noting that in both of these diagrams, I was making no attempt at being exhaustive, nor was I expecting these designs to survive beyond an initial spike. But because moving boxes and arrows around on a whiteboard is easier than rewriting code, I tend to start off any moderately complex project this way.

With just these two whiteboard sketches, I had most of what I needed to start coding. The only important thing left to be done before I could fire up my text editor was coming up with a suitable name for the game. After trying and failing at finding a variant of “All your base” that wasn’t an existing gem name, I eventually settled on “Stack Wars.” I picked this name because a big part of the physical game has to do with building little stacks of army tiles in the territories you control. Despite the fact that the name doesn’t mean much in the electronic version, it was an unclaimed name that could easily be CamelCased and snake_cased, so I decided to go with it.

As important as naming considerations are, getting bogged down in them can be just as harmful as paying no attention to the problem at all. For this reason, I decided to leave some of the details of the game in my head so that I could postpone some naming decisions until I saw how the code was coming together. That decision allowed me to start coding a bit earlier at the cost of having a bit of an incomplete roadmap.

Picking some low-hanging fruit

Every time I start a new project, I try to identify a small task that I can finish quickly so that I can get some instant gratification. I find an early success to be important for my morale, and it also serves as a gentle way to test some of my assumptions about the project.

I try to avoid starting with the boring stuff like setting up boilerplate code and building trivial container objects. Instead, I typically attempt to build a small but useful end-to-end feature. For the purposes of this game, an ASCII representation of the battlefield seemed like a good place to start. I started this task by creating a file called sample_ui.txt with the contents you see here:

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB

0 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

1 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

2 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

3 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

4 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

5 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

6 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

7 (B 2)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

8 (___)--(W 2)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

WWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWW

In order to implement this visualization, I needed to make some decisions about how the battlefield data was going to be represented, but I wanted to defer as much of that work as possible. After asking for some feedback about this problem, I opted to write the visualization code against a simple array of arrays of Ruby primitives that could be trivially be transformed to and from JSON. Within a few minutes, I had a script that was generating similar output to my original sketch:

require "json"

data = JSON.parse(File.read(ARGV[0]))

color_to_symbol = { "black" => "B", "white" => "W" }

header = " 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8\n"

separator = " | | | | | | | | |\n"

border_b = " BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB\n"

border_w = " WWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWW\n"

battlefield_text = data.map.with_index do |row, row_index|

row_text = row.map do |color, strength|

if color == "unclaimed"

"(___)"

else

"(#{color_to_symbol[color]}#{strength.to_s.rjust(2)})"

end

end.join("--")

"#{row_index.to_s.rjust(3)} #{row_text}\n"

end.join(separator)

puts [header, border_b, battlefield_text, border_w].join

Although this script is a messy little hack, it got me started on the project in a way that was immediately useful. In the process of creating this visualization tool, I ended up thinking about a lot of tangentially related issues. In particular, I started to brainstorm about the following topics:

- What fixture data I would need for testing various game actions

- What the coordinate system for the

Battlefieldwould be - What data the

Territoryobject would need to contain - What format to use for inputting moves via the command-line interface

The fact that I was thinking about all of these things was a sign that my initial spike was successful. However, it was also a sign that I should spend some time laying out the foundation for a real object-oriented project rather than continuing to hack things together as if I were writing a ball of Perl scripts.

Laying out some scaffolding

Although you don’t necessarily need to worry about writing super-clean code for a first release of a project, it is important to at least lay down the basic groundwork, which makes it possible to replace bad code with good code later. By introducing a TextDisplay object, I was able to reduce the stackwars-viewer script to the following code:

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

require "json"

require_relative "../lib/stack_wars"

data = JSON.parse(File.read(ARGV[0]))

puts StackWars::TextDisplay.new(data)

After the initial extraction of the code from my script, I thought about how much time I wanted to invest in refactoring TextDisplay. I ended up deciding that because this game will eventually have a GUI that completely replaces its command-line interface, I shouldn’t put too much effort into code that would soon be deleted. However, I couldn’t resist making it at least a tiny bit more readable for the time being:

module StackWars

class TextDisplay

COLOR_SYM = { "black" => "B", "white" => "W" }

HEADER = "#{' '*7}#{(0..8).to_a.join(' '*6)}"

SEPARATOR = "#{' '*6} #{9.times.map { '|' }.join(' '*6)}"

BLACK_BORDER = "#{' '*5}#{COLOR_SYM['black']*61}"

WHITE_BORDER = "#{' '*5}#{COLOR_SYM['white']*61}"

def initialize(battlefield)

@battlefield = battlefield

end

def to_s

battlefield_text = @battlefield.map.with_index do |row, row_index|

row_text = row.map do |color, strength|

if color == "unclaimed"

"(___)"

else

"(#{COLOR_SYM[color]}#{strength.to_s.rjust(2)})"

end

end.join("--")

"#{row_index.to_s.rjust(3)} #{row_text}\n"

end.join("#{SEPARATOR}\n")

[HEADER, BLACK_BORDER, battlefield_text.chomp, WHITE_BORDER].join("\n")

end

end

end

After writing this code, I wondered whether I should tackle the building of a proper Battlefield class that would take the raw data for each cell and wrap it in a Territory object. I was hesitant to make both of these changes at once, so I ended up compromising by creating a Battlefield class that simply wrapped the nested array of primitives for now:

module StackWars

class Battlefield

def self.from_json(json_file)

new(JSON.parse(File.read(json_file)))

end

def initialize(territories)

@territories = territories

end

def to_a

Marshal.load(Marshal.dump(@territories))

end

# loses instance variables, but better than hitting to_s() by default

alias_method :inspect, :to_s

def to_s

TextDisplay.new(to_a).to_s

end

end

end

With this new object in place, I was able to further simplify the stackwars-viewer script, leading to the trivial code shown here:

require_relative "../lib/stack_wars"

puts StackWars::Battlefield.from_json(ARGV[0])

The benefit of doing these minor extractions is that it makes it possible to focus on the relationships between the objects in a system rather than their implementations. You can always refactor implementation code later, but interfaces are hard to untangle once you start wiring things up to them. This is why it is important to start thinking about the ingress and egress points of your objects as early as possible, even if you’re still allowing yourself to write quick and dirty implementation code.

The benefits of laying the proper groundwork for your project and keeping things nicely organized are hard to see in the early stages but are extremely clear later when things get more complex.

Starting to chip away at the hard parts

Unless you are an incredibly good software designer, odds are good that some aspects of your project will be harder to work on than others. There is even a funny quote that hints at this phenomenon: “The first 90 percent of the code accounts for the first 90 percent of the development time. The remaining 10 percent of the code accounts for the other 90 percent of the development time.”

To avoid this sort of situation, it is important to maintain a balance between easy tasks and more difficult tasks. Starting a project with an easy task is a great way to get the ball rolling, but if you don’t tackle some challenging aspects of your project early on, you may find yourself having to rewrite a ton of code later. The hard parts of your project are what test your overall design as well as your understanding of the problem domain.

With this in mind, I knew it was time to take a closer look at some of the game actions in Stack Wars. Because the FORTIFY action must be implemented before any of the other game actions become meaningful, I decided to start there. The following code was my initial stab at figuring out what I needed to build in order to get this feature working:

def fortify(position)

position.add_army(active_player.color)

active_player.reserves -= 1

end

Until this point in the project, I had been avoiding writing formal tests because I had a mixture of trivial code and throwaway code. But now that I was about to work on some Serious Business, I decided to try test-driving things. After a fair amount of struggling, I decided to add mocha into the mix and begin test-driving a Game class through the use of mock objects:

require_relative "../test_helper"

describe "StackWars::Game" do

let(:territory) { mock("territory") }

let(:battlefield) { mock("battlefield") }

subject { StackWars::Game.new(battlefield) }

it "must be able to alternate players" do

subject.active_player.color.must_equal :black

subject.start_new_turn

subject.active_player.color.must_equal :white

subject.start_new_turn

subject.active_player.color.must_equal :black

end

it "must be able to fortify positions" do

subject.expects(:territory_at).with([0,1]).returns(territory)

territory.expects(:fortify).with(subject.active_player)

subject.fortify([0,1])

end

end

Taking this approach made it possible for me to test whether the Game class was able to delegate fortify calls to territories, even though I had not yet implemented the Territory class. It gave me a pretty nice way to look at the problem from the outside in and resulted in a clean-looking Game class:

module StackWars

class Game

def initialize(battlefield)

@players = [Player.new("black"), Player.new("white")].cycle

@battlefield = battlefield

start_new_turn

end

attr_reader :active_player

def fortify(position)

territory = territory_at(position)

territory.fortify(active_player)

end

def start_new_turn

@active_player = @players.next

end

private

def territory_at(position)

@battlefield[*position]

end

end

end

However, the problem remained that this code hinged on a number of features that were not implemented yet. This frustration caused me to begin working on getting the basic functionality in place for a Territory class without writing tests for its behaviors up front. I used a combination of the stackwars-viewer tool and irb to verify that the Territory objects that I had shoehorned into the system were working as expected.

After making it so that the Battlefield object contained a nested array of Territory objects, I went back and wrote some unit tests for Territory. The tests ended up being fairly long and tedious, but the implementation code for Territory#fortify ended up being quite simple and worked as expected:

module StackWars

class Territory

# other methods omitted

def fortify(player)

if controlled_by?(player)

player.deploy_army

@army_strength += 1

@occupant ||= player.color

else

raise Errors::IllegalMove

end

end

end

end

Getting the Territory tests to go green felt good, but I wasn’t satisfied. Now that I had implemented a game action, I wanted to see it in real use. This itch lead me to write a simple script that simulated players fortifying their positions, which resulted in the following output:

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

WWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWW

0 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

1 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

2 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

3 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

4 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

5 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

6 (B 2)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

7 (___)--(W 2)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

8 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB

Fortifying black position at (0,6)

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

WWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWW

0 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

1 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

2 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

3 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

4 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

5 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

6 (B 3)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

7 (___)--(W 2)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

8 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB

Fortifying white baseline position at (2,0)

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

WWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWW

0 (___)--(___)--(W 1)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

1 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

2 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

3 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

4 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

5 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

6 (B 3)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

7 (___)--(W 2)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

| | | | | | | | |

8 (___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)--(___)

BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB

Seeing this example run gave me a great feeling because it was the first sign that something resembling a game was under development. However, the path to get to this point was long and arduous, even though this was by far the easiest action to implement.

Slamming into the wall

There comes a time in every reasonably complicated project at which you end up biting off more than you can chew. The exact reason for this will vary from project to project: perhaps you overlooked something in your design, or misunderstood a key requirement, or maybe you just let your code get too messy and it reached a point where it could no longer be extended without heavy refactoring. This sort of thing is normal and to be expected, but is also a critical turning point in your project.

If you aren’t careful, the setbacks caused by slamming into the wall can really shake your spirits and negatively affect your productivity. Having unrealistic expectations that a certain task will be easy to complete is a surefire way to trigger this effect. That’s what happened to me on this project; I hope the following story will serve as a cautionary tale.

After implementing the FORTIFY action, I thought I would be able to repeat the process for MOVE, ATTACK, and INVADE. Anticipating this approach, I roughed out a replacement for Game#fortify() called Game#play(), which took into account all game actions and selected the right one based on the circumstances:

def play(pos1, pos2=nil)

if pos2.nil?

territory = territory_at(pos1)

territory.fortify(active_player)

else

from = territory_at(pos1)

to = territory_at(pos2)

raise Errors::IllegalMove unless battlefield.adjacent?(from, to)

if to.occupied_by?(opponent)

attack(from, to)

else

move_army(from, to)

end

end

start_new_turn

end

However, as soon as I looked at this method definition, I knew for sure that testing this code with mocks would be at best brittle and at worst downright misleading. On top of that, the code introduced several new concepts that would need to trickle down into the rest of the system. I tried to think through how to simplify things so that this could be more easily tested, but quickly grew frustrated and ended up abandoning the idea of test-driving this functionality.

Instead, I decided that the problem was that I didn’t have a running game console that displayed the battlefield and accepted inputs. I thought that even a buggy system that allowed me to interact with the game in a tangible way would be better than writing a ton of tedious tests against what might end up being the wrong interface. This decision caused me to begin to modify the system in any number of haphazard ways until I got a functioning game console.

I did eventually get something working, but it was so fragile that I ended up enlisting my wife’s help in QA testing it until it sort of looked and felt like a working game. Unfortunately, the hot fixes I was applying while she found new ways to break things caused more bugs to surface. Eventually, I gave up on the project for the evening and decided to come back to it with fresh eyes in the morning.

Searching for a pragmatic middle path

Conventional wisdom says that if a particular bit of code is especially hard to test, a structural flaw in your design might be to blame. Because testability and extensibility are linked together, it is a good idea to listen to your tests when they make life hard for you. But there certainly are times when we need to temporarily sacrifice purity in the name of practicality.

The fact that I had a working Stack Wars implementation but no confidence that it wasn’t super buggy left me in a sticky position: I wanted to make sure that the code would stabilize, but I didn’t want to rework the design from scratch. The base design of the code was more than good enough for a first release; I just wanted to iron the wrinkles out and find a way to refactor with a bit of confidence that each change I made wasn’t going to break everything all over again.

To accomplish this goal, I started by making my manual testing process more efficient. I made it so that my game console would fire up a game in which each player had only 2 armies in reserve rather than 27. This change made it possible to play an entire game in a fraction of the time that a real game would take, but still allowed me to test all the game actions. I used this faster manual feedback loop to quickly eliminate the bugs that I had introduced the night before, and I also tried to be more careful about the fixes I applied.

Once I got things to a reasonable level of stability, I realized that I could then build a fairly good integration test by replaying moves from a real, complete game. After a few more tweaks, my wife and I managed to make it through a game without a crash. I then set up a demo script that would replay these moves one by one until it reached the end of the game. Once I got that stage working, I extracted it into an integration test that reads the moves from a JSON file, calls Game#play for each one, and then does some validations to make sure the game ended as expected:

describe "A full game of stack wars" do

let(:moves) do

moves_file = "#{File.dirname(__FILE__)}/../fixtures/moves.json"

JSON.load(File.read(moves_file))

end

let(:battlefield) { StackWars::Battlefield.new }

let(:game) { StackWars::Game.new(battlefield) }

it "must end as expected" do

message = catch(:game_over) do

moves.each { |move| game.play(*move) }

end

message.must_equal "white won!"

white = game.active_player

black = game.opponent

battlefield.deployed_armies(white).must_equal(4)

battlefield.deployed_armies(black).must_equal(0)

white.reserves.must_equal(0)

black.reserves.must_equal(0)

white.successful_invasions.must_equal(6)

black.successful_invasions.must_equal(4)

end

end

Having this integration test in place will make it possible for me to come back later and refactor the codebase to make it more testable without the fear of breaking things. Although unit tests offer more in the way of documenting how the codebase is meant to work and provide more precisely located feedback upon failure, this single test is good enough to ensure that I don’t introduce new critical bugs into the application without noticing them.

In retrospect, it seems like integration testing is more important than exhaustive unit testing in the very early phases of a hard-to-test project. It is less of a time investment to create some black box testing and such testing is less likely to be thrown out as subsystems change rapidly during the initial phases of development.

Shipping the 0.1.0 release

It is important to remember that a 0.1.0 release of an open source project is basically just a way to communicate an idea to your fellow programmers. If you label a release 0.1.0, no one is going to expect feature completeness, stability, or even a particularly high level of code quality. What they will expect is for you to have attempted to make your project comprehensible to them and ideally to have done a good job of making it easy to get involved in your project. I tried to keep these priorities in mind while preparing Stack Wars for release.

Adding the full game test was an important first step for making the codebase release-ready. People who try out the game are going to want to be able to submit bug reports and possibly add new bits of functionality. Without tests to verify that their changes don’t break stuff, it would be much harder to safely accept their contributions.

Some additional code cleanup was also necessary: I removed a bunch of tests and examples that were no longer relevant and shifted around some of the code within each class to make it easier to read. In general, it is a good idea to remove anything that is not actively in use, as well as anything that isn’t quite working correctly whenever you release code. This step lessens the chances of confusion and frustration when someone tries to read your code.

I did not bother with API documentation just yet because so much is still subject to change, but I did write up a basic README with instructions for those who want to play-test the game as well as those who might want to hack on its code. I also wrote a detailed writeup of the game rules because folks will need to learn the game before they can understand how this program works.

In addition to documentation and cleanup, I did what I could to make it very easy to try out the game. Running stack_wars rules will display the game rules so that you don’t need to go back to the source code or your web browser to know how the game is played. Additionally, I made it possible to run through the sample game that Jia and I played just by typing stack_wars demo. The sole reason these features exist is to make the software more accessible to new users, which I hope will increase the chance that those users become contributors at some point in the future. But even if most people download my software without ever contributing to it in some way, I still care a lot about the experience they have while using something I created.

You can try things out for yourself by following the instructions in the README; this video will give you a sense of what the first release of this project ended up looking like:

Although in the grand scheme of things it may not look like much, I am pretty happy with it for a 0.1.0 release!

Reflections

The more I think about it, the more I realize that the cycle I’ve outlined in this article is pretty much the one I go through whenever I’m starting a new project. There are some things about my process that I like, and some things that I don’t. However, knowing that there is a pattern I tend to follow makes me think that I can now work towards optimizing it over time.

The thing I found fascinating about this exercise is that it really drove home the point that software development is about a lot more than just writing code. There are a whole range of skills involved in bringing a software project from the idea phase to even the most humble first release, and it seems like it’d be good for us to spend time optimizing the whole process rather than just our purely code-oriented skills.

Because I’ve never attempted anything quite like this exercise before, I’m really curious to hear your thoughts on this article. Please leave a comment, even if you’re the type that typically lurks, with whatever your initial gut reaction may be. If this is a topic that interests you, please also share your thoughts on how we might be able to dig even deeper in future experiments.

Practicing Ruby is a Practicing Developer project.

All articles on this website are independently published, open source, and advertising-free.